One of the biggest changes I glossed over fairly quickly in my last blog post was the introduction of the Entity Component System (ECS) pattern to Ripple’s codebase. For this blog post I thought I’d dive in a little deeper into what the ECS pattern is and what my specific recipe for baking it into Ripple’s code looks like.

While most of my blog posts are targeted at anyone who is interested in the game, this is a more technical post and will focus on programming architecture and implementation details.

What Is ECS?

Well let’s take a step back and give some context for why the ECS pattern exists and what problems it addresses.

Composition Over Inheritance

At its core the ECS pattern boils down to “composition over inheritance”. If you’ve ever taken a software architecture course or have been programming longer than a year it’s a design principle you’ve probably ran into before. Basically whenever you rely heavily on inheritance trees, given enough changes, you’ll end up in a situation where adding a new class requires refactoring large parts of the tree to allow the new class to fit into the existing hierarchy. In short, inheritance is often not very flexible.

If you’re looking for a more a thorough overview of the problems the ECS pattern solves and how an existing object-oriented approach would change with its introduction, I would take a look at the Component chapter from the wonderful Game Programming Patterns book by Bob Nystrom.

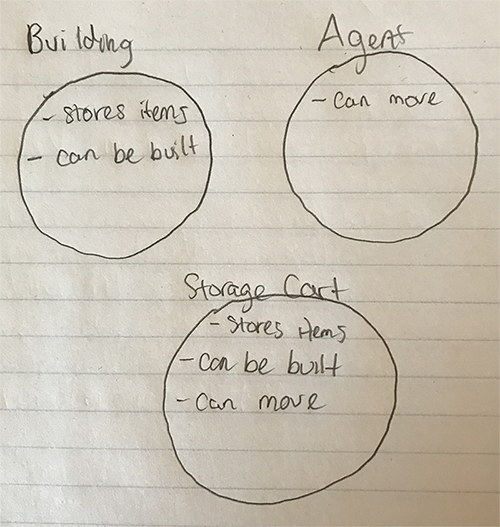

An example from Ripple’s development was when I was thinking about adding a StorageCart class to the game. I already had a Building class which encompassed the relevant functionality like storing items inside the building and having the building be constructed. This seemed like a good class to inherit from because a storage cart does both of those things. But a storage cart is slightly different in that it also can move, whereas a building cannot. Well, buildings can’t move but I had an Agent class that did have this behavior.

At this point, I had several choices on how to implement the StorageCart class if I wanted to stick with the object-oriented, class hierarchy approach:

- Have each class be separate. This is obviously the worst choice as it requires duplication for every shared piece of functionality.

- Have the

StorageCartclass extend theBuildingclass. TheStorageCartclass ends up sharing most of theBuildingclass’ functionality but then has to duplicate the movement-handling code from theAgentclass. Again, not great because there’s still duplicated code.

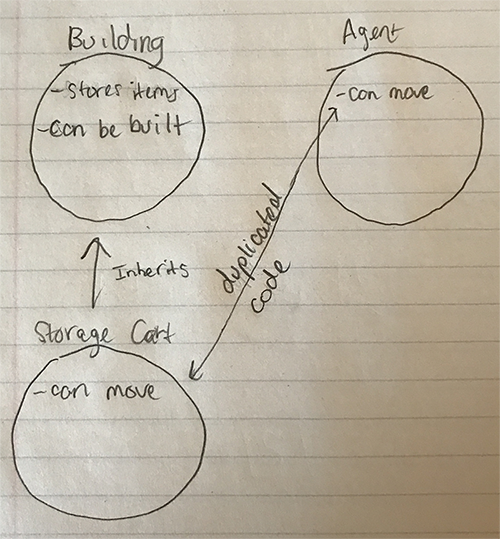

- Pull all the shared functionality between the

StorageCartclass and both theAgentandBuildingclasses out into some shared class,EntityThatDoesEverything. Then have all three classes inherit fromEntityThatDoesEverything. While, there’s no duplication with this solution there are two problems. 1) The child classes end up doing nothing. 2) Given enough classes being added,EntityThatDoesEverythingwill in fact do everything and thus will turn into a bloated, monolithic class. Not great.

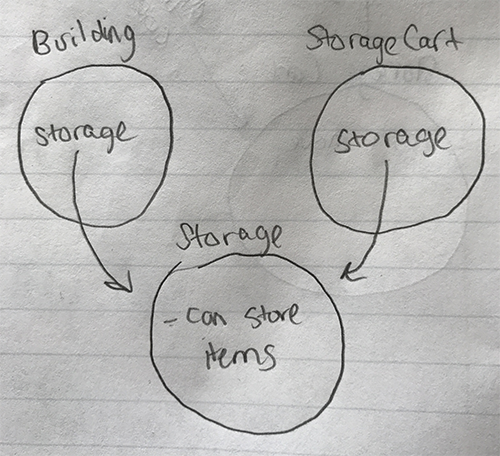

None of these seem great so let’s try out the “composition over inheritance” approach. If we did that, instead of having classes inherit their functionality from their class or their parent-class, the functionality would be encapsulated as a separate class by itself. Given the previous example then StorageCart and Building would both have storage functionality because they would instantiate an instance of the Storage class.

Why is this better? Well, because we’re no longer duplicating functionality. If we need to update the behavior for the storing items, we just update the Storage class. One place for all our changes and all the changes get propagated to our StorageCart and Building classes.

No duplication and we’re also not moving all the functionality into a single monolithic class. The drawbacks of having a large monolithic class for all our functionality are 1) you have a very large class which in and of itself can be very hard to navigate. And 2) any class that extends from the monolithic class will have a bunch of functionality and methods that that child class doesn’t need. Again, this can lead to confusion and bugs (e.g. “why is my Car class able to call a ‘fly’ method?”).

OK But Where Does ECS Come In?

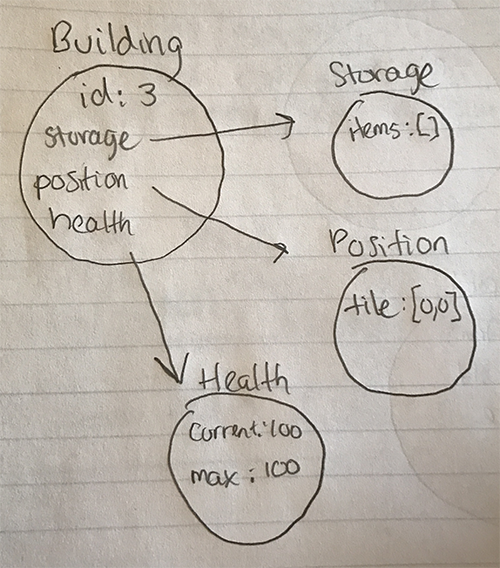

I mentioned you could separate out different pieces of functionality into different classes and then have those classes attached to your entities. If we did this with every piece of functionality our entity classes would essentially be nothing more than an id and pointers to other classes that implement all of their needed functionality. This is the core of the ECS pattern.

To be more explicit, the core parts of the ECS pattern are Entities, Components, and Systems. And in ECS, this id is the Entity. Components are raw data representing one piece of functionality for Entities and are tied to each Entity by its id. This would be our Storage class from the previous example or the Position, Health, and Storage bubbles from the above diagram. Systems, which are aligned to a specific type of Component, perform updates on each Component of their type every turn (StorageSystem operates on StorageComponents).

Ripple ECS Architecture

If you’re not familiar with ECS that super brief intro might have confused you. I figure it will be more illuminating to give a more thorough explanation of each piece as it exists in my implementation so I’m not repeating myself. So let’s jump in.

I imagine there are a whole bunch of different ways to implement the ECS pattern so, caveat emptor, this is just one way of implementing it.

Entities

The first pieces of the puzzle are entities, the most simple concept to grapple with. Entities are your objects in game: monsters, buildings, bullets, etc. [1] An entity in ECS is an id with a number of components tied to it. When I say a component is tied to an entity’s id I just mean, given the id, you can fetch any component for that entity. There is no entity class and there are no pointers. Think of it as a primary key in a database.

Components

Components are also very simple. They are just structs that represent an entity’s state for a given piece of functionality. What does that mean? Well, let’s look at an example.

interface IHealthState {

maxHealth: number;

currentHealth: number;

}

Ripple is written in TypeScript and all the code examples will follow suit.

This is the interface for the state of one of the simpler components in the Ripple codebase, the Health component. It contains all the relevant data for keeping track of an entity’s health. In this case we just need to know the current health and the max health of the entity. If you wanted to do damage to an entity you would fetch this component, using the entity’s id, and decrement the currentHealth value. We’ll get to the specifics of how that works in a bit.

You might be confused by the interface being called IHealthState instead of IHealthComponent. This is really an implementation detail. I decided to have components exist as wrapper objects containing a reference to the actual state and then some extra metadata like the name of the component. This was done to make identifying the components in code a bit easier.[2] Here’s the full file for context to see what I’m talking about:

import {ComponentEnum} from '../component-enum';

// This is the component wrapper definition

export interface IComponent {

enum: ComponentEnum;

name: string;

state: {[key: string]: any;}

}

// The state for the HealthComponent

export interface IHealthState {

maxHealth: number;

currentHealth: number;

}

// Declaring our Health component as an instance of the

// component wrapper class

export interface IHealthComponent extends IComponent {

state: IHealthState;

}

// The HealthComponent instantiated with default values (null)

export const Health: IHealthComponent = {

name: 'health',

enum: ComponentEnum.Health,

state: {

currentHealth: null,

maxHealth: null

}

};

When working with components in Ripple you’ll almost always be working with instances of the state property on the Component class. The wrapper mostly exists for the overall ECS implementation behind the scenes.

Systems

We have our Entity ids and Component state objects so where do Systems come in? As I said before, a System is associated with a specific type of component and is in charge of performing any necessary updates on components of that given type. For instance you might have a PoisonComponent and a PoisonSystem that’s associated with it. The PoisonSystem might check the PoisonComponent of a given entity for an isActive flag and then decrement the health value for that entity every turn.

Not every component needs to have a system associated with it. A system only needs to exist if a given component requires an update method to check it every turn. For example, the HealthComponent I showed has no associated System in Ripple. It is mostly manipulated and updated by other Components’ Systems.

In its most simple form a System might look like this:

class EntitySystem {

update (entities: number[]) {

entities.forEach(entity => {

// do stuff with entity every turn

});

};

}

The core of the System is the update method. It is called once per tick by the engine and this is the only way the System is interacted with by outside code. Any other methods on the System exist solely to accomplish operations that occur inside of the update method. Each call to the update method includes the list of entities of the System’s given type. To reiterate, the entities passed in each have a Component of the given System’s type attached to them. A PoisonSystem therefore would receive all entity ids for which the associated entity has a PoisonComponent.

Putting the core pieces together

A simple example showing the interaction between Entities, Components, and Systems in the ECS pattern might look like this:

// Generate a new unique id, this is our entity

// Maybe it's a monster or something since it has health

// and can be poisoned

const entity: number = createEntity();

// Instantiate a HealthComponent and PoisonComponent. Internally

// this will tie the component to the entity with id `entity`

createComponent(entity, HealthComponent);

createComponent(entity, PoisonComponent);

// This is the PoisonSystem

// Somewhere in our game engine code, the `update` method

// will be called every turn and passed in the matching entities

class PoisonSystem {

update (entities: number) {

entities.forEach(entity => {

// Get the PoisonComponent state

const poisonState = getComponent(entity, PoisonComponent);

// If they're poisoned

if (poisonState.isActive) {

// Get the HealthComponent state

const healthState = getComponent(entity, HealthComponent);

// Decrement their health

healthState.currentHealth -= 1;

}

});

}

}

// Poison the entity by fetching its PoisonComponent using its

// id and setting `isActive` to true

// At this point the PoisonSystem's `update` method will start

// decrementing the entity's health

const poisonComponent = getComponent(entity, PoisonComponent);

poisonComponent.isActive = true;

Assemblages

Well, we’ve gotten through the core pieces of the ECS pattern but I have some extra pieces that I’ve rolled into my implementation. The first of these are called Assemblages and are essentially templates for different types of entities.

First, a little context. Let’s say we want to have a Ball entity with a Move component, so it bounces and changes position properly, a Render component, so it shows up on the screen correctly, and a Color component, so balls can be different colors.

When you’d construct a Ball entity, you’d need to instantiate each of those three components so that it has the desired functionality. As a result you’d end up doing something like this:

const ball: number = createEntity();

createComponent(ball, Components.Move);

createComponent(ball, Components.Render);

createComponent(ball, Components.Color);

That means every time we create a ball we need to construct one of each of these three components. This is pretty tedious and it becomes even more tedious the more types of entities and components you add to the game. This is where assemblages come into play.

An assemblage really is just a list of components that make up a given entity to make spawning them easier. For our ball example it would look like this:

const ballAssemblage = [

Components.Move,

Components.Render,

Components.Color

];

// Now we can create a ball in two lines

const ball: number = createEntity();

ballAssemblage.forEach(component => createComponent(ball, component));

Assemblage Data

Now we have an easy way to create entities of the same type in a jiffy, but what happens if we want to create entities of the same type but with different values for their components? With our ball example, we have a way to create a bunch of balls with an assemblage very easily but how do we create a bunch of green balls and a bunch of red balls just as easily?

The previous code example would create a Ball with default values for each component. Depending on how you defined your components, this might mean you have a Ball with no color that hasn’t been spawned or rendered yet.

First, let’s lay out what the components look like and the API for creating components with state values already set:

class ColorComponent extends Component {

name = 'Color';

state: {

color: string = 'none';

}

}

// Method to create a component with state values

createComponent(

entityId: number,

component: Component,

state: any

): void;

// This call would create a ColorComponent for the ball with

// color set to "red"

createComponent(ball, Component.Color, { color: 'red' });

With that laid out, the solution to easily create a ball of a certain color is probably pretty obvious. We just need a way to map component state values to each component. More specifically, we need a way to map the color “red” to the ColorComponent.

// We're mapping the desired state values for the Color

// component to the "name" property, "Color", on that component

redBallAssemblageData = {

Color: { color: 'red' }

// We could also include any other component's state

// like the MoveComponent:

// Move: { velocity: 10 }

};

// We can still create a red ball in a few lines

const ball: number = createEntity();

ballAssemblage.forEach(component => {

createComponent(

ball,

component,

redBallAssemblageData[component.name]

);

});

The key in the above code working is this:

redBallAssemblageData[component.name]

The name property on the Component wrapper class finally fulfills its purpose by mapping the proper state value entry in the assemblage-data map to its matching component.

The beauty of this is that, looking at redBallAssemblageData, you can see that defining various types of entities can be done with plain old JSON. Using simples lists (Assemblages) and JSON (Assemblage-data) we can very easily define scores of entity types as well as variations within the same entity type. (As long as you make sure to keep your component’s state objects composed entirely of primitives.)

Utils

Systems have methods to perform updates on components but this is only within the context of the System’s update method. What happens if we want to update a component from outside the System? Or what if a System needs to update a component not of its given type? This is where Utils come in.

Utils are tied to a Component of a certain type similar to Systems but provide publicly accessible methods for performing updates on that component type. They exist as a good location to consolidate logic relevant to a certain Component without tying it to a System, whose methods can’t be shared.

It sounds like some implementations choose to just leave this job up to the Systems themselves. I chose to introduce Utils as way to keep Systems focused on just performing updates every turn via the update method to keep in line with the “single responsibility principle”.

One use-case for Utils is for the use of more complicated data structures for your Components’ state. Ideally Components should be made up of primitive data structures [3]. Therefore, since they have no methods attached to them, if you want to use more advanced data structures you’ll need a place to store that logic outside the component itself. Utils are a good spot for this code.

Entity Manager

The final piece of the puzzle with my specific implementation of ECS is the Entity Manager. This is, as it sounds, a class that manages all entities and all components. It provides an API to create components for an entity, get components for an entity, delete components for an entity, etc. In short a lot of the methods used in the above examples would be on the Entity Manager class: createEntity() -> entityManager.createEntity(). The Entity Manager is also the one in charge of calling every System’s update method with the appropriate entities every turn.

But How Do You Use It?

Those are a lot of pieces and it might be confusing how they come together. So far I’ve given some small isolated examples so here’s a couple more involved examples that should help paint a more concrete idea of how the architecture is used in practice.

Creating a villager in Ripple

The first example is how to create a villager in Ripple. Every call to create an entity begins with a method on the EntityManager. In this case that method is createEntityFromAssemblage. This call takes care of creating all the required components associated with that assemblage and tying them to the newly created entity. This is basically that forEach loop going through each Component in an Assemblage in one of the previous examples.

At this point our entity has all of its components but they are all populated with default data and thus mostly empty. Therefore the next step is to initialize the entity’s components with its specific assemblage data, that is, the data that makes a villager a villager as opposed to an orc or something else. This is fairly simple and involves just a few steps of fetching components and then merging their state values with the assemblage data.

What if we want to spawn a villager with a specific name or some other attribute? Well, just as easily as we merged in the assemblage data we would then merge in the desired villager’s name as a component’s state value. Merging all this data might look something like this behind the scenes:

// Merging VillagerComponent data

// Default, empty component data

const defaulComponentData = { eyeColor: null, hair: null };

// Assemblage data i.e. defaults for the villager entity type

const assemblageComponentData = { eyeColor: 'blue', hair: 'red' };

// This would be passed in by the user making the call to spawn the

// entity with their desired component values

const specificComponentData = { hair: 'brown', name: 'Chet Manley' };

// End result with villager entity data extended with user's specified

// data

const entityData = _.merge(defaultComponentData, specificComponentData);

// { eyeColor: 'blue', hair: 'brown', name: 'Chet Manley' }

Since a lot of this logic is repeated and most of the time you just want to spawn something of a given type with only a couple attributes changed, I pulled this code out into an EntitySpawner class with simple methods like spawnBuilding(data: EntityData). In this case, the spawnBuilding method would take care of passing in the assemblage and assemblage-data for the Building entity type, and then would merge in any extra, specific data for the given entity via the data parameter.

How to move an entity on the screen

If you’ve read up till this point you probably have a pretty good idea of how to do this. All you need to do is fetch the component in charge of keeping track of an entity’s position in game, let’s say it’s the PositionComponent, and then update the coordinates or tile of this component’s state. But how does this result in the entity actually moving on the screen?

Well obviously this will differ from engine to engine, but from a high level it might go something like this:

- Update the tile on the

PositionComponentfor the entity.

const positionState = getComponentForEntity(

entity,

Component.Position

);

positionState.tile = newTile;

-

RenderableSystemin charge of theRenderableComponentof the same entity sees the tile changed on thePositionComponentfor that entity. -

RenderableSystemupdates the coordinates for the entity’s sprite on screen to match up with the new tile.

class RenderableSystem {

update (entities) {

entities.forEach(entity => {

const positionState = getComponentForEntity(

entity,

Component.Position

);

// 2. PositionComponent tile updated

if (positionState.currentTile !== positionState.previousTile) {

const renderableState = getComponentForEntity(

entity,

Component.Renderable

);

// 3. Update our sprite position

renderableState.spritePosition = positionState.currentTile;

}

})

}

}

This is a pretty basic example but it highlights a couple key things. First, it shows how systems operate on their components to produce changes in game. In this case the RenderableSystem updates the RenderableComponent and this causes the sprite to move on screen.

Second, it shows how a component’s system can gather data from other components to update the state of components that they are in charge of. More explicitly, while the RenderableSystem is in charge of updating the RenderableComponent it can use data from the entity’s other components, in this case the PositionComponent, to update the RenderableComponent.

Pros and Cons

Now that you have have an idea of how the ECS pattern works in practice, I thought I’d take some time to lay out, at a high level, some of the costs and benefits I’ve found from using it.

Pros

Deterministic updates through immutable state

One of the great things about the ECS pattern is how simple performing and tracking updates is. Updating components is as easy as changing a value on their state. There’s no varying API spread across different classes; it’s always the same no matter what you’re trying to update.

Tracking changes is just as easy. You make a change to a component and then in your System’s update loop you check to see if the component changed since the last time update was called. If you go a step further and make components immutable, updates become easier to detect and less error prone. Either way there’s definitely no reliance on confusing and hard to keep track of event bindings to detect mutations in state.

Data-oriented design

Saving and loading information is easy with ECS because components are just data. That means in JavaScript land, as long as you stick to primitives, you can dump your entire game’s state to JSON via JSON.stringify. You could even store it to localStorage if you want. Loading is just as easy as calling JSON.parse on your dumped JSON data and then iterating and recreating entities from the data.

On top of this, adding new types of entities can be as simple as adding a map with some strings and numbers in it. Want to add a green zombie? Well it’s probably as easy as just copying and pasting the existing zombie’s JSON data and adding the string ‘green’ somewhere. This means you don’t need a programmer to add content to the game.

ECS encourages isolated functionality

One of the core ideas behind ECS is that every piece of functionality in your game can and should be isolated and turned into a single component. Since functionality is often isolated, when you go to update a piece of functionality you don’t have to worry as much about your changes breaking other functionality.

Not hindered by iterative development

ECS is quite flexible so you don’t need to plan out the entire game up front. This is as opposed to inheritance trees where, if you don’t plan all your classes up front, adding new ones can be quite costly in terms of development time. This means you can be quite agile with how you add features to your game.

Cons

Boilerplate

Every time I add a new component I have to update a bunch of lists and enums to have it be properly included in all the various pieces a part of the ECS framework. (This is likely an implementation detail and could be reduced if you’re clever.)

Can be expensive/inefficient if you’re lazy

I mentioned the update method of Systems being passed every entity with the given Component of that System’s type. Obviously if you don’t take care to organize data structures to make that fetch fast you can handicap performance. In addition, if you don’t take care to only update the entities you need to you can destroy performance just as easily.

In short, you’ll have to be smart with how you organize the underlying data structures and systems that operate at scale in your ECS implementation.

Can be confusing at times

There’s numerous cases since I’ve started working with the ECS pattern where there’s ambiguity in terms of what’s the best way to do something. Here’s some examples of those types of situations.

“Where do updates happen”/”Who’s in charge of what”? In the case of the RenderableSystem reading the PositionComponent and using it to update the RenderableComponent, it could have been done the opposite way. I.e. the PositionSystem sees the tile was updated and then updates the RenderableComponent directly. It’s unclear which is better so you’ll have to rely on your experience and judgement.

“Who gets to touch what”? It seems clear to me that some components by necessity interact with other components. A PoisonComponent probably needs to interact with a HealthComponent. Other times it’s unclear if components should be kept separate. Having interconnected components can break the isolation which is one of the benefits of using ECS in the first place.

“Who goes first?” Order matters when calling the update method on Systems if you want deterministic code. If your systems are not called in the same order every time you cannot expect components to be updated consistently. Given that fact, sometimes it can be unclear which systems should go before others. For example it seems pretty clear that the system in charge of rendering should go last but other systems can be more ambiguous.

Final Thoughts

When I initially heard about ECS I thought it sounded a bit too complicated. Why invest in building and integrating a fairly substantial framework and opinionated architecture when objects “just work”? Well an object-oriented approach did “just work” until it “totally did not work”. While the object-oriented approach was very fast to get up and running with, the long-term costs in time spent refactoring and rewriting code started to add up till adding certain features became a seemingly insurmountable endeavor. It got to the point where I put off features I absolutely should have been working on just because the thought of breaking yet another core system left me apathetic.

While I’m sure everyone will have a different experience with ECS depending on their personal tastes as a programmer and the type of game they’re working on, overall I’ve found ECS to be a godsend for Ripple’s development. Ripple is a simulation game with a lot of interacting systems. ECS has been a huge help by focusing on isolating those various systems. This was a large improvement over my previous object-oriented approach where many classes covered many overlapping domains of functionality leading to confusion and bugs.

On top of this, the flexibility of ECS has been a huge boon as it really fosters iterative development. Now I can easily introduce and try out new features/functionality as components and then get rid of them if they don’t work out. This means I spend less time on implementing features that might be a dead-end in terms of fun.

I hope this post convinces some people to try out the Entity Component System pattern or helps some to understand it a bit better. If anyone is interested in using my JavaScript/Typescript ECS implementation just shoot me a message on Twitter or via email and I can get to work on pulling out the code into a GitHub repository.

As always feel free to hit the subscribe link in the header/footer if you want to stay up to date on Ripple’s development and/or see more posts like this one.

Footnotes

https://www.reddit.com/r/gamedev/comments/519j3n/ecs_tipstricks_just_getting_into_ecs_what_should/d7amlve/ 2. There's an example of this at the end of the "ASSEMBLAGE DATA" section. 3. This makes it easier to use immutable structs for component-state and it means you can trivially dump game data to JSON for saving and loading.